QUOTE:

"No man is complete without a feeling for music

and an understanding of what it can do for him."

and an understanding of what it can do for him."

AUTHOR: Zoltan Kodaly

MEANING OF THE QUOTE:

"Complete fulfillment in life is not possible

unless you have some music appreciation."

unless you have some music appreciation."

COMPOSER:

FREDERIC CHOPIN

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2,

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2,

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

1st Movement: Maestoso

Artur Rubinstein, Piano

Andre Previn, Conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2,

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

2nd Movement: Larghetto

Artur Rubinstein, Piano

Andre Previn, Conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2,

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

3rd Movement: Allegro Vivace

Artur Rubinstein, Piano

Andre Previn, Conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

COMPARE DIFFERENT

PERFORMANCES

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2,

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

3rd Movement: Allegro Vivace

Alfred Cortot, Piano

John Barbirolli, Conductor (1935)

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2,

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

3rd Movement: Allegro Vivace

Evgeny Kissin, Piano

Myung-Whun Chung, Conductor

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R1CZUY9Qowc

SEE THE 2ND MOVEMENT

PERFORMED IN

A BALLET FORMAT

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2,

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

2nd Movement: Larghetto

From Ballet 'La Dame aux Camelias'

Performed by the Paris Opera Ballet

Orchestra of The Opera national de Paris

OP. 2 IN F-MINOR

2nd Movement: Larghetto

From Ballet 'La Dame aux Camelias'

Performed by the Paris Opera Ballet

Orchestra of The Opera national de Paris

CONCERTO DEFINITION

The instrumental concerto is a music

composition (often a symphonic-type work)

in most cases, features a solo instrument

(in special cases more than one) with an

orchestra ensemble accompaniment (or

piano accompaniment) where the soloist is

ascribed a leading role showing off his/her

virtuosic skill while the accompaniment (of

some sort) forms a background to it.

|

| Chopin's Parents: Justyna and Nicolas |

Frederic Chopin, the son of a French

father and Polish mother, was born and

grew up in Poland but after the collapse

of the Polish revolution against Russia in

1831, he went into exile to France settling

in Paris which at that time was then

a center for Polish emigres.

The Polish-Russian War of 1830-1831 was

essentially an armed rebellion of a

politically partitioned Poland against the

Russian Empire. Although the Polish

resistance was able to achieve some minor

victories, the Imperial Russian Army quickly

crushed the uprising. With Poland an

integral part of Russia, Warsaw became

"little more than a military garrison" meaning

the immediate closure of the university and

the Warsaw Conservatory where Chopin

had, merely months before, just completed

a musical course of study with Józef Elsner

| Józef Elsner |

graduating from the conservatory showing

"exceptional talent and musical genius."

Even though he started his composition

work at the age of 12 with Elsner, director

of the Warsaw Conservatory, in 1822, his

pianistic talent had been recognized even

earlier; just before his eighth birthday he

had appeared in public playing a concerto

of Gyrowetza and had already begun

composing little piano pieces. When Elsner

took him on as a student it was his hope

that the gifted Chopin would one day com-

pose the great Polish national opera. How-

ever, he soon realized that Chopin needed

to find his own unique voice as a pianist

and composer and not wanting to impose

his own influence over that need, he gave

Chopin the freedom to explore his interest

in Polish folk music and expanding musical

forms like the polonaise and mazurka as

well as the nocturne and waltz.

By the time Chopin was 19, in 1829,

| Chopin in 1829 |

he began to expand his musical horizons

by traveling outside his native Poland. In

August of that year he made his Viennese

debut impressing audiences with his

brilliant piano playing and his novelty

as a Polish nationalistic composer.

Chopin debut in Vienna,

July 31, 1829

|

The summer of 1829 found the 19 year old

Chopin returning to Poland. Exhaused

from his Viennese trip he stopped along the

way at Prince Radziwill's estate at Antonin,

| Duke Antoni Radziwiłł’s Estate in Antonin, Greater Poland |

While resting there, he sketched out the

F-Minor Concerto (his first attempt at

composing in a large form) before

returning to Warsaw where he con-

centrated on finishing it early in 1830.

| Henryk Siemiradzki: Chopin Plays for the Radziwiłłs in 1829, 1887 |

As was often the case with composers

in the Romantic Era (and still is today),

the inspiration for the Concerto came to

Chopin as the result of an requited love;

the object of his affection being a soprano

voice student at the Warsaw Conservatory.

For whatever reason, Chopin chose not

to reveal his feelings to the young woman

for a long time. Instead, he poured his

heart out to his dearest friend,

Tytus Woyciechowski,

|

(1808–1879)

|

in a letter dated October 3, 1829,

confessing that his Adagio from the

F-Minor Concerto had been inspired

by tender feelings for one

Konstancja Gladkowska,

|

(1810-1889)

|

"whom I dream of."

Chopin, swooning like a love-struck

adolescent, also stated

"I have, perhaps to my misfortune, already

found my ideal, which I worship faithfully

and sincerely. Six months have elapsed,

and I have not yet exchanged a syllable

with her of whom I dream every night.

Whilst my thoughts were with her I

composed the Adagio of my [F-Minor]

concerto, and this morning she inspired

the waltz [Op. 70, No. 3] which I

send along with this letter."

Konstancja met Chopin on April, 21, 1829,

during a concert of the soloists of the

Warsaw conservatory, where she was

studying voice with Carlo Soliva. Her

chance encounter with Chopin, a fellow

student, left no impression on her even

though Chopin was absolutely smitten.

When Chopin left Warsaw, not long after

this concerto was completed, he and

Konstancja exchanged friendship rings.

Considering their relationship simply a

fond friendship, she married someone

else the following year. Not until decades

later, long after Chopin's death, by reading

it in his biography, did she findout about

the deep feelings he had felt for her.

Though this Concert was inspired by Chopin's

feelings for Konstancja Gładkowska, when it

was published, six years later after he had

long forgotten about her, it had a dedication

to his pupil, Countess Delphine Potocka,

a long time friend and gifted singer.

|

(1805-1877)

|

In 1830, Delphine met Chopin in Dresden

and in 1832 she settled in Paris where she

became his student. Their close relationship

often fueled gossip regarding their alleged

love affair however in the mid 20th Century,

love letters to support this claim were

deemed false. Yet, it was she,

"one of the most admired types of society queens,"

in Franz Lizst's opinion, who

was with him when he died.

Chopin, now a young graduate of the

Warsaw Conservatory, was seeking to

establish himself in the musical world. He

was talented, ambitious, and in love. All

three of these qualities found reflection in

his Piano Concerto in F Minor, Op. 21.

Although know as his Second Piano

Concerto, this work pre-dates, by about

half a year, Chopin's Concerto in E Minor,

Op. 11, which now bears the designation

"Piano Concerto No. 1."

The two concertos were published in

reverse order of their composition

resulting in a misleading impression

of their chronology. It was published

second because during his extended

journey moving from Warsaw to Paris

in 1830-31, the orchestral parts were

lost and had to be written out again.

Chopin, finding this task very tedious,

completed doing this after his actual

second concerto, the E Minor Concerto,

was already in print (published in 1833

in Paris and Leipzig). Despite being

performed in 1830 the F-Minor Concerto

was not published until 1836.

Before the first public performance for

the debut of his concerto he had two

semi-private rehearsal performances in

the Chopin family's drawing room:

the first in February, among family and

|

| Chopin Family Drawing Room |

close friends; the second on March

3rd in the presence of the musical elite

|

Piano Teacher of Chopin

|

On that occasion the orchestra part was

performed by a small chamber ensemble

conducted by Karol Kurpinski

| Conductor: Karol Kurpinski |

and the solo piano part was played, of course,

by Chopin. Just two weeks later those

performances were repeated in public

ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE CONCERT

"The universal wish

of music lovers

is to be granted:

Mr. Szope (Chopin),

so rightfully adored,

whose talent is compared by

connoisseurs with

the foremost virtuosos,

is shortly to give a piano concert

at the National Theatre,

performing works

of his own composition."

of music lovers

is to be granted:

Mr. Szope (Chopin),

so rightfully adored,

whose talent is compared by

connoisseurs with

the foremost virtuosos,

is shortly to give a piano concert

at the National Theatre,

performing works

of his own composition."

on the grand stage of the

National Theatre in Warsaw

| The Interior of the First National Theatre |

|

K. F. Dietrich: Plac Krasińskich, First Half of 19th C.

(This building is now occupied by the Warsaw Rising Monument)

|

for its premiere concert on March 17, 1830.

That occasion proved a critical success for

the young composer, then barely 20 years

old, acclaiming him as a Polish national hero

with one writer (in reference to the great

virtuoso Italian violinist) dubbing Chopin

"the [Niccolò] Paganini of the piano."

|

| Niccolò Paganini |

Another contemporary account recorded:

"How beautifully he plays. What fluency!

What evenness! Impossible that there

should exist a more perfect concord

between two hands. He plays with such

certainty, so cleanly that his Concerto

might be compared to the life of a just man:

no ambiguity, nothing false. His music is full

of expressive feeling and song, and puts

the listener into a state of subtle rapture,

bringing back to his memory all the

happy moments that he has had."

After the premiere Chopin reflected:

"The first Allegro of my concerto, un-

intelligible to most, received the award

of a single 'Bravo' but I believe this was

given because the public wished to show

that it understands and knows how to

appreciate serious music. There are

people enough in all countries who like

to assume the air of connoisseurs!"

"The Adagio (Larghetto) produced a very

great effect, after this, the applause and

'Bravos' really came from the heart."

Both of Chopin's completed piano

concertos emerged from a one-year

burst of musical ingenuity from 1829-

30. Some early biographers report

(as witnessed by numerous refer-

ences in his correspondence through-

out the 1830's that Chopin even con-

sidered composing a third concerto. It

apparently never progressed beyond

the planning stage as it is thought

that he abandoned the idea after

composing just one movement of it.

In 1841, he brought out a piece called

the Allegro de Concert, Opus 46 which

might possibly had been fashioned out

of the remnants of that abandoned third

concerto. The music was strangely

regressive and phenomenally difficult,

written in a style reminiscent of the

flamboyant Liszt. It was quite unlike his

two published concertos and not con-

sidered on of his most popular

or well known works.

Barbara Hesse-Bukowska, Piano

(1958)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2UBqRDrEkTo

http://www.usc.edu/dept/polish_music/PMJ/issue/3.1.00/bonkowski_rink.html

http://www.usc.edu/dept/polish_music/PMJ/issue/3.1.00/bonkowski_rink.html

Because Chopin knew that performing

his own music was the accepted route

to stardom for young virtuosic performers,

the primary impetus in composing the

concerto was to showcase his own

pianistic abilities on a debut tour through-

out Europe. He knew that his growing

public fully expected him to follow the

path established by Mozart and

Beethoven so he tried to combine

the piano with the orchestra, not only

in creating his two piano concertos, but

also in composing the Variations Op. 2,

Fantasia Op. 13, Concert Rondo Op. 14,

and the Grand Polonaise Op. 22. Being

still uncomfortable with composing

orchestrations, after age 20, he never

again wrote for a large ensemble.

Composing for an orchestration presented

problems for Chopin as his chosen

medium was the instrument and he was

relatively inexperienced at writing for

large ensemble accompaniments. As a

result his piano parts were of a quality of

undeniable genius while music written for

the other instruments was often deemed

somewhat unbalanced in a lopsided

manner. Chopin did not seem to care as

he homed in on one aspect of composition

and intensely devoted himself to it

emphasizing the piano virtuosity and

relegating the orchestra to the background,

almost as an afterthought, rather than being

in dialogue as an equal partner with the piano.

About this Chopin wrote:

in dialogue as an equal partner with the piano.

About this Chopin wrote:

"Mozart encompasses the entire domain

of musical creation, but I've only got the

keyboard in my poor head. I know my

limitations, and I know I'd make a fool of

myself if I tried to climb too high without

having the ability to do it. They plague me

to death urging me to write symphonies

and opera, and they want me to do every-

thing in one- a Polish Rossini and a Mozart

and a Beethoven. But I just laugh under my

breath and think to myself that one must

start from small things. I am only a pianist."

The few works Chopin wrote for piano

and orchestra are often criticized for their

orchestra writing. There were some harsh

comments by the famous composer/master

orchestrator Hector Berlioz,

| Hector Berlioz |

in which he complained that when in

these concertos Chopin calls upon the

orchestra to play all at once,

"they cannot be heard, and one is tempted

to say to them: why don't you play for heaven's

sake! And when they accompany the piano,

they only interfere with it, so that the listener

wants to cry out to them: be quiet, you

bunglers, you are in the way!"

He also referred to Chopin's

treatment of the orchestra as

In a formal sense, Franz Liszt

| Franz Liszt |

in 1852 suggested that,

"Chopin did violence to his genius every

time he sought to fetter it by formal rules."

By this he probably meant that the usual

larger classical treatment formats were

incompatible with his imagination and

therefore every time he tried to stick to

composing within the confines of a strict

structure his art would suffer.

Despite the criticism, Chopin's two piano

concertos were designed, un-apologetically,

as display vehicles for himself to show off

his virtuosity (just like all other traveling

piano soloists were doing during this time

period) and not composed with the

intention of renovating the standard

concerto format. This lightly orchestrated

accompaniment background, allowing the

solo line to dominate throughout, made

this concerto a functional piece for this

purpose because it gave Chopin the

freedom to perform this piece as a solo,

without any accompaniment at all,

whenever he needed to.

Within the confines of the secondary

ensemble accompaniment, Chopin does

explore some interesting orchestral tech-

niques. A noted example in the third move-

ment of this concerto being the use of col

legno; a technique where string players

strike the string with the stick of the bow

rather than using the hair side creating an

interesting percussive effect. For the day,

this was a very innovative way of

using string instruments.

| Col Legno |

COL LEGNO

As his guiding influence in orchestration,

Chopin turned to several earlier con-

temporaries (composers not that well

known today) to model his style after;

composers with a concerto style very

contrary to the more equal and ad-

versarial relationship between soloist and

orchestra found, for instance, in Beethoven

Concertos. Theirs was a conception of the

concerto being a loosely organized show-

case for the performer to display their

virtuosity. It was a different tradition (a style

of piano music which became popular in

the early 19th Century) shaped by a textural

technique called "stile brillante" to which

Chopin took its virtuosity and it expanded it

to a pinnacle that it had never been before

not only in technical requirements but in his

use of personal expression. By doing this

he helped lead the way into the

Among some of the composers

whose decorated concertos were popular,

effective scores that were themselves updated,

flashy models derived from Mozart's concertos

and those by Kalkbrenner and Herz.

| Friedrich Kalkbrenner (1785–1849) |

Achille Devéria:

Henri Herz (1803-1888),

1832

|

He was also influenced by others; composers

of the Italian bel canto opera tradition, most

especially the great bel canto master,

(Bellini and Chopin were friends as well as

colleagues and in their compositions both men

prioritized showing off the melody over under-

stated harmonic accompaniments.)

and John Field,

|

| John Field |

the Irish composer known for developing

the nocturne and cultivating it both as an

idea and a genre inescapably associat-

ing it forever with the piano.

ing it forever with the piano.

Philadelphia Orchestra: Eugene

Ormandy/Arthur Rubinstein

Ormandy/Arthur Rubinstein

This F-Minor Concerto is a large-scale

(approximately 30 minutes) master-

piece laid out in three movements and

follows the classical concerto traditional

structure of fast-slow-fast (to a certain

extent) with an instrumentation scored

for solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2

clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2

This work made extensive use of Polish themes

as Chopin had always been fascinated by

as Chopin had always been fascinated by

the rhythms and melodic vitality of Polish

folk music (especially the mazurka);

something extremely evident in the

concerto's finale. This concerto is challeng-

ing and demands a mastery of piano

technique and musicality from the performer.

In fact, its solo piano part is so well supplied

with highly ornamented stylistic displays that

no cadenza (cadenzas are normally found in

concertos to show off the performer's skill)

was deemed necessary to convince an

audience of the soloist's virtuosity.

MOVEMENT I

Maestoso in F-Minor

A Majestic Introduction

Maestoso

The first movement (Maestoso) is

The first movement (Maestoso) is

structured as a simple and straight-

forward double-exposition form, a

variant of the classical sonata-allegro

form dating back to the 18th Century.

It is a form typically employed in the

keyboard concertos of Mozart and

other Classical Period composers.

Chopin begins his work with an

orchestral exposition (an exposition

presents the themes) and keeping

with the convention established in

concerto allegros, the themes are

shown first in the orchestra. With an

impressive entrance made by the piano,

due in part to the sudden sparse back-

ground of the orchestra accompaniment,

the music comes to life dominating the

texture entirely while the orchestra retreats

to a supporting accompaniment role. The

solo instrument, now in full charge of the

music, changes the atmosphere by explor-

ing and commenting on the thematic ideas

just previously introduced by the ensemble

in a far more elaborate fashion; more

distinctive, poetic, and endlessly inventive.

Stated Chopin biographer Frederick Niecks:

|

| Frederick (Friedrich) Niecks |

"Quite uncharacteristically of this sort of

composition for its time, in comparison to

the examples Chopin modeled his concertos

after, is his musical lyricism (a sort-of poetic

cantilena) which is far more warmly expressive

and poignant. This is Chopin's personality,

his distinctive style, taking over in the music."

MOVEMENT II

Larghetto

in a key relative to F Minor

(i.e. A-flat)

An Endearing Piece

Early Romantic virtuoso concertos tend

to suffer from mundane token slow

movements, but this famous Larghetto

uncharacteristically (lying at the innermost

core of the entire concerto) is a personal

heartfelt interlude conceived as an

expression of his love; a splendid tribute

with lovely, rich lyrical themes, gliding

ornamentation, magical harmonies, and

unparalleled pianistic sonorities.

Critics have called this an

"exquisite tone poem, in which extremes

of emotion are expertly juxtaposed."

The music, with its sweet, melancholy

(radiantly beautiful and serene) character,

is a nocturne for soloist and orchestra

influenced in part from the nocturnes of

John Field. Its seemingly endless fluid

lines, elaborate ornamentation, and

recitative-type passages are in the form

of a grand da capo aria showing the

influence of the contemporaneous Italian

(bel canto style) opera composer,

Vincenzo Bellini, whose music works

Chopin greatly admired after having

heard them while on trips made to

Berlin in 1828 and 1829.

|

| Berlin |

The movement's format has a

simple ternary (A‑B‑A) outline

SECTION A:

A soulful nocturne.

SECTION B:

A more passionate middle section

played over tremolo strings

that Chopin decorates with

extraordinary freedom.

SECTION A:

The nocturne returns and

the movement closes in a

wistful, dreamy fashion.

beginning with a long and tender

theme that appears after a brief

mysterious orchestral introduction.

said that it

"sounds like the opening of a gate

to some haven of love and peace."

this next portion of the work builds to

an exquisitely languid and passionate

(romantic style) melody that could

double as an opera aria (an instrumen-

tal version of a vocal aria) for the piano

soloist. The piano melody is so rhapsodic

and embellished that it sounds almost

improvised. After all the trills and decor-

ations, Chopin gets down to the real heart

of the movement in what has become one

of the most quoted of his melodies (the

principal theme). It appears twice more

(three times all together). On each

occasion, Chopin has it played very

delicately, yet each time he impressively

arranges it in new, increasingly airy orn-

aments. The third time the phrase, ori-

ginally comprising eight notes, builds up

in the form of a wave, expressed by a

Agitated, violent sonorities then burst into

the music stating a famous dramatic pas-

sage in the middle section in which an

emotionally melodic line, led in octave

unison, appears in the piano against

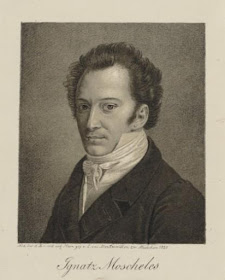

Among those composers (those who were

influential to Chopin) to use a piano against

an orchestral background in a similar

in his Concerto in G Minor,

Ignaz Moscheles

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 3

IN G MINOR, Op 58

Michael Ponti, Piano

Othmar Maga, Conductor

Philharmonica Hungarica

Ignaz Moscheles

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 3

IN G MINOR, Op 58

Michael Ponti, Piano

Othmar Maga, Conductor

Philharmonica Hungarica

| Ignacy Dobrzynski |

Ignacy Dobrzyński

PIANO CONCERTO

IN A-FLAT MAJOR,

OP. 2 (1824)

Emilian Madey, Piano

Lukasz Borowicz, Conductor

Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra

The piano and orchestra carry the

music to a wrenching climax before

the opening mood returns with an

unexpected bassoon solo, imitating

This larghetto remained one of

Chopin's favorites and excited the

admiration (and praise for its

and Franz Liszt who himself des-

cribed the second movement's time-

stopping beauty, from agitation

to passion, as

"...of a perfection almost ideal, its

expression, now radiant with light,

MOVEMENT III

Allegro Vivace in F Minor

A Lively Ending

Chopin, writing this composition in the

autumn and winter of 1829, took his

time kneading its final closing third

movement into satisfactory shape.

Chopin first mentions this concerto in

a letter, written on October 3, 1829,

to his friend Titus Woyciechowski

confiding to him that his teacher Elsner

"has praised the Adagio of my concerto. He

says it is original; but I don't wish to hear any

opinions on the Rondo just yet as I am

The music is arranged in a three-part,

rondo-like form, with several sharply

contrasting themes in a mazurka-type

style. He was inspired by Polish

country folk dances: the vibrant

mazurka and its slightly slower cousin,

the kujawiak (with their playfully off-

kiltered, skewed rhythms) to which he

became directly acquainted with while

spending his vacations, between 1824-

1828, in the rural areas of Poland. The

striking of the strings with the stick of

the bow, the pizzicato and the open

fifths of the basses appear to show that

Chopin preserved the atmosphere

Chopin created much more interest in

these original folk dances by expanding

their form and composing them around

brilliantly musical stylized settings; he

changed them so wonderfully into

something of his own creation.

The traditional mazurka was in triple

time accompanied by strong accents

on the second or third beat (when

danced, the accents are reinforced by

a strong tap of the heel). It originated

as a Polish folk dance in triple meter

from the Mazovia district near Warsaw.

But the mazurka became an umbrella

name for a number of related dances:

the fiery mazurek, the lively oberek or

the slower and more sentimental

kujawiak. All three dances originated

from the older polska, a dance in which

a strong accent falls on the second or

third beat of the measure, accompanied

by a tap of the heel.

The opening key of the Rondo finale

is F-minor, a key that is slightly senti-

mental, with a tinge of reflection but

the Concerto ends by shaking itself

out of that reflection, nostalgia and

reverie, when an unexpected

conspicuous solo horn call,

marking a sudden shift from minor to

major ends the piece in the cheerful

key of F-major. This heralds in a brief

coda (marked "brillante") displaying an

array of the pianist's spectacular pyro-

technic virtuosic skills building up to a

climax after which a short fragment of

the main mazurka theme is heard again.

A final flourish by the soloist and

ending chords by the orchestra

conclude the piece.

The distinctly Polish flavor of this

movement caused Warsaw

audiences to hail this concerto

as an expression of their nationalist

hopes. One review of the work's

premiere in the Polish capital stated:

"More than once these tones seem to be

the happy echo of our native harmony.

Chopin knows what sounds are heard in

our fields and woods, he has listened to the

songs of the Polish villager, he has made it

his own and has united the tunes of his

native land in skillful composition

and elegant execution."

|

| Albert Baumann: Chopin Concerto Numero II, 2005 |

LINKS

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d6inF7uFBB8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DaBiz03ceSE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIIG4GN4xP

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m9DC-h38CGg

http://www.chopinmusic.net/works/concerti/

http://muswrite.blogspot.com/2014/08/chopin-piano-concerto-no-2-in-f-minor.html

http://www.interlude.hk/front/youthful-poetrychopin-piano-concerto-no-2-in-f-minor-op-21/

http://cso.org/uploadedfiles/1_tickets_and_events/program_notes/040810_programnotes_chopin_pianoconcerto2.pdf

http://www.sfsymphony.org/Watch-Listen-Learn/Read-Program-Notes/Program-Notes

/CHOPIN-Concerto-No-2-in-F-minor-for-Piano-and-Orch.aspx

http://www.seattlesymphony.org/symphony/buy/single/programnotes.aspx?id=10679&src=t

http://www.mso.org/plan_your_experience/program_notes/classics_4

http://tso.ca/Plan-Your-Experience/Programme-Notes/Piano-Concerto-No-2-in-F-Minor-Op-21/Print.aspx?ID=1837

http://www.santarosasymphony.com/09_10_events/event_classical_5.asp

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:LLi-YE5cNSQJ:racinesymphony.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/

Program-Notes-for-March-9-20141.doc+&cd=7&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

http://www.sco.org.uk/content/piano-concerto-no-2-f-minor-op-21?print=1

http://en.chopin.nifc.pl/chopin/composition/detail/id/66

http://www.kcsymphony.org/ResourceCtl?fileId=AuFpgbGH%2BJN1JRYk0kWkQw%3D%3D

http://www.hhso.org/program-notes/chopin-sibelius/index.htm

http://www.ridgefieldsymphony.org/program-notes-2012-sept-22/

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:VchW0Wxs2WUJ:

www.liverpoolphil.com/download.php%253Fid%3D195+&cd=18&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

http://www.boulderphil.org/BPOProgramNotes3-17-10.pdf

http://facstaff.uww.edu/allsenj/MSO/NOTES/1415/5.Feb15.html

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:zeQA4l5ENosJ:

www.houstonsymphony.org/tickets/media/upload/pdf/sub18programnotes.pdf+&cd=30&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

http://www.tacomasymphony.org/client/assets/files/Classics%20III_11-12_TSO.pdf

http://www.orsymphony.org/concerts/1314/programnotes/cl13.aspx

http://www.kimmelcenter.org/events/notes/item/0809/ViennaPhil_feb09.pdf

http://magnumopus.manifo.com/frederic-chopin

http://www.carnegiehall.org/berlininlights/themusic/8160.html#top

http://www.manchestersymphonyorchestra.com/concerts/058/058-1.html

http://bazawiedzy.chopin2010.pl/

http://www.coindumusicien.com/

http://www.chopin.pl/edycja_1999_2009/galeria/gall-22.html

http://www.library.yale.edu/musiclib/exhibits/chopin/second_concerto_op21.html

http://www.usc.edu/dept/polish_music/PMJ/issue/3.1.00/bonkowski_rink.html

http://www.laphil.com/philpedia/music/piano-concerto-no-2-frederic-chopin

http://www.bbc.co.uk/orchestras/pdf/con_prog_aberdeen150313.pdf

http://en.chopin.nifc.pl/festival/edition2013/concerts/day/all

http://www.radiochopin.org/episodes/item/550-radio-chopin-episode-91-nocturne-in-f-sharp-major-op-15-no-2

http://interlude.jumpwebdev.com/front/youthful-poetrychopin-piano-concerto-no-2-in-f-minor-op-21/

http://nyphil.org/~/media/pdfs/program-notes/1415/Chopin-Piano-Concerto-No-2.pdf

https://archive.org/details/imslp-concerto-no2-op21-chopin-frdric

http://www.seattlesymphony.org/symphony/buy/single/programnotes.aspx?id=10679&src=t

http://www.mso.org/plan_your_experience/program_notes/classics_4

http://tso.ca/Plan-Your-Experience/Programme-Notes/Piano-Concerto-No-2-in-F-Minor-Op-21/Print.aspx?ID=1837

http://www.santarosasymphony.com/09_10_events/event_classical_5.asp

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:LLi-YE5cNSQJ:racinesymphony.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/

Program-Notes-for-March-9-20141.doc+&cd=7&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

http://www.sco.org.uk/content/piano-concerto-no-2-f-minor-op-21?print=1

http://en.chopin.nifc.pl/chopin/composition/detail/id/66

http://www.kcsymphony.org/ResourceCtl?fileId=AuFpgbGH%2BJN1JRYk0kWkQw%3D%3D

http://www.hhso.org/program-notes/chopin-sibelius/index.htm

http://www.ridgefieldsymphony.org/program-notes-2012-sept-22/

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:VchW0Wxs2WUJ:

www.liverpoolphil.com/download.php%253Fid%3D195+&cd=18&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

http://www.boulderphil.org/BPOProgramNotes3-17-10.pdf

http://facstaff.uww.edu/allsenj/MSO/NOTES/1415/5.Feb15.html

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:zeQA4l5ENosJ:

www.houstonsymphony.org/tickets/media/upload/pdf/sub18programnotes.pdf+&cd=30&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

http://www.tacomasymphony.org/client/assets/files/Classics%20III_11-12_TSO.pdf

http://www.orsymphony.org/concerts/1314/programnotes/cl13.aspx

http://www.kimmelcenter.org/events/notes/item/0809/ViennaPhil_feb09.pdf

http://magnumopus.manifo.com/frederic-chopin

http://www.carnegiehall.org/berlininlights/themusic/8160.html#top

http://www.manchestersymphonyorchestra.com/concerts/058/058-1.html

http://bazawiedzy.chopin2010.pl/

http://www.coindumusicien.com/

http://www.chopin.pl/edycja_1999_2009/galeria/gall-22.html

http://www.library.yale.edu/musiclib/exhibits/chopin/second_concerto_op21.html

http://www.usc.edu/dept/polish_music/PMJ/issue/3.1.00/bonkowski_rink.html

http://www.laphil.com/philpedia/music/piano-concerto-no-2-frederic-chopin

http://www.bbc.co.uk/orchestras/pdf/con_prog_aberdeen150313.pdf

http://en.chopin.nifc.pl/festival/edition2013/concerts/day/all

http://www.radiochopin.org/episodes/item/550-radio-chopin-episode-91-nocturne-in-f-sharp-major-op-15-no-2

http://interlude.jumpwebdev.com/front/youthful-poetrychopin-piano-concerto-no-2-in-f-minor-op-21/

http://nyphil.org/~/media/pdfs/program-notes/1415/Chopin-Piano-Concerto-No-2.pdf

https://archive.org/details/imslp-concerto-no2-op21-chopin-frdric